"A place of rest where we know we will not enter..."

Trois Mélodies, op. 91 by Mel Bonis (1858-1937)

As I considered repertoire for my Doctoral chamber music recital in January 2023, I settled on the theme of love, partly because it was impossible to avoid. I can’t describe the countless songs I’ve sung in various languages, either extolling the sweet overtures of first love or the bitter pain of rejection. For this project, I found myself drawn to a specific aspect of love: the eternal conflict between idealizing the object of our affections and the messier realities of loving another human being.

Little did I know how deeply this tension would inform the life and mélodies (songs) of French composer Mel Bonis (1858-1937).

Music, this divine language, translates all beauty, all truth, all ardor. The object of our eternal wishes takes a form; music holds out its arms to us and yet, it is far, very far away and we will not reach it. It is like the threshold of a garden of delights where everything is illuminated and perfumed, a place of rest where we know we will not enter.

FROM SOUVENIRS ET RÉFLEXIONS (1974); ADAPTED FROM MEL BONIS' NOTEBOOKS

I encountered Bonis’ song repertoire by chance on L’Heure Rose: Musique des Femmes, a fantastic 2014 album with soprano Hélène Guilmette and pianist Martin Dubé. To listen to L’Heure Rose, featuring mélodies by late nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century women composers including Mel Bonis, Augusta Holmès, Pauline Viardot, Amy Beach, Cécile Chaminade, and Lili Boulanger, click below.

As I listened to L'Heure Rose, Bonis’ Trois Mélodies, op. 91 stood apart with the lyric contour of their melodies and their surprising harmonic progressions. I found myself drawn to a romantic sensibility deeply embedded within Bonis’ music.

It is often mentioned that the act of mapping biographical events onto a composer's creative choices can be a superficial exercise. However, in the case of Mel Bonis, as I learned more about her biography, her song compositions seemed inextricably intertwined with the ever-unfolding elements of her life.

A forbidden romance, a secret daughter, the struggle to balance her role as a wealthy bourgeois mother with her musical career, and the gendered prejudice that distorted her professional life...

I wondered how the composer truly felt as she set Maurice Bouchor's poetry in Trois Mélodies, texts which outline the poet's desire for an unattainable beloved.

In turn, I wondered if Trois Mélodies could be considered as an entry in Bonis' diary. By examining these songs in greater detail, we could perhaps reveal some aspect of the emotional life of the composer herself, whose music has long been overlooked.

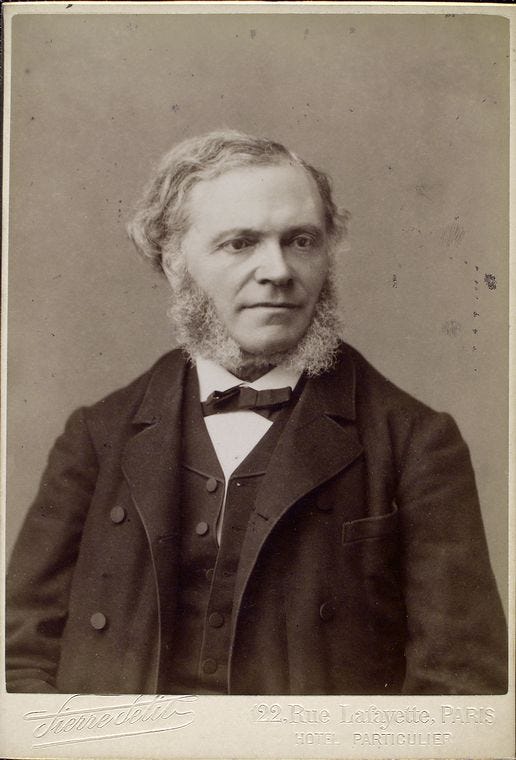

Mélanie Bonis (1858-1937)

Mélanie Bonis was born into a Parisian lower middle-class family. Her father, Pierre-François Bonis (1826-1900), was a foreman in a luxury watchmaking factory, and her mother, Marie Anne Clémence Mangin (1836-1918), worked as a textile trimmer from the family home.1

With her sister Eugénie-Caroline, Bonis was raised in a strict Catholic household, a religion she would devoutly practice for the rest of her life. Her parents had little interest in music and actively discouraged her musical education. Bonis’ musical aptitude, though, was apparent as a child, and she taught herself to play the piano.

In Souvenirs et Réflexions, a posthumous memoir assembled by Bonis’ daughter Jeanne Brochot from her mother’s notebooks, the composer recalls her fraught and ecstatic relationship to music, which she cultivated from a young age.

I would like to be able to describe the state of mind that is at once so distressing, torturous, and delicious into which music plunges me - the music that I love. I should be able to do it, I experienced this sharp sensation to the point of pain so much, even as a child (I could say, especially as a child). It was then like an agony of aspirations towards happiness, a tension, of every sensitive, cordial being, towards a thing which smiles upon us and slips away at the same time.2

At twelve years old, Bonis’ parents allowed their daughter music theory and piano lessons at home. After a family friend's introduction, Bonis took private lessons with eminent composer César Franck (1822-1890), who was impressed by her musical abilities. Bonis' parents finally consented in 1877 to her enrollment at the famed Paris Conservatoire; she was eighteen years old.

At the Conservatoire, Bonis would study piano accompaniment, harmony, and counterpoint with Ernest Guiraud (1837-1892) and August Bazille (1828-1891). Her classmates included composers Claude Debussy (1862-1918) and Gabriel Pierné (1863-1937), although instruction was often separated by gender.3 Bonis excelled in her musical pursuits, securing second prize in harmony and accompaniment in 1879 and first prize in harmony in 1880.4

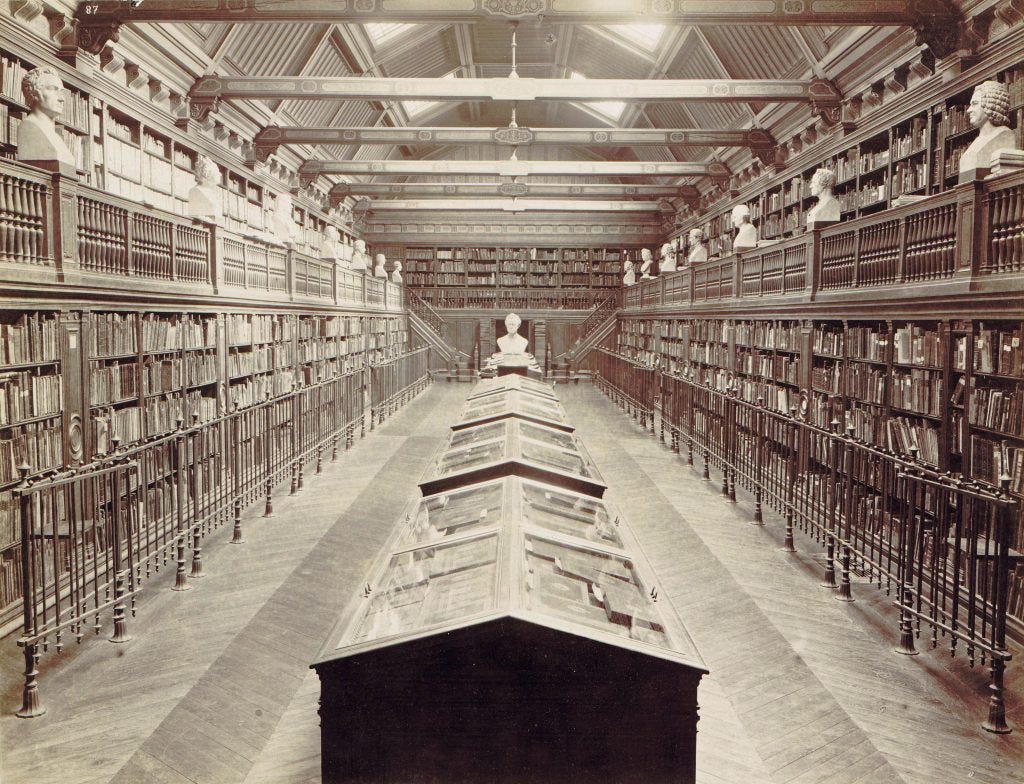

While Bonis was part of a generation of French women with growing access to public life, she faced considerable setbacks in her pursuit of a professional career, particularly with limited networking opportunities and blatantly gender-biased assessments of her musical abilities. We can imagine the learning environment for women musicians at the Conservatoire from the 1895 photo below: a stately room, filled with musical scores and centuries of knowledge, guarded in perpetuity by busts of the so-called "great men."

Unlike her male counterparts, Bonis could not submit compositions for the illustrious Prix de Rome, which was barred to women applicants until 1903.5 Pianist Christine Géliot, great-granddaughter of Mel Bonis and founder of the Association Mel Bonis, recounts a biting remark, passed down through oral history. After hearing Mel Bonis' string quartet in 1905, composer Camille Saint-Saëns observed to painter Jean Gounod, "I didn't know a woman could write that. She knows all the ins and outs of a being a composer!"6

During her time at the Conservatoire, it is no wonder that Mélanie Bonis adopted the compositional alias of Mel Bonis. By removing feminine connotations from her name, Bonis attempted to ward off this gendered prejudice, as she sought the publication and public performance of her musical works.7

Watch and listen to pianist Diana Sahakyan's beautiful interpretation of "Desdémona" from Femmes de Légende on her eponymous 2022 album.

Femmes de Légende, a collection of Bonis' piano portraits composed over fifteen years, was published by Furore in 2003. Bonis' seven solo piano works were inspired by female figures from ancient mythology, legends, or plays, including Desdemona, Ophelia, Mélisande, and Salome.

While accompanying voice lessons at the Conservatoire, Bonis met fellow student Amédée Landély Hettich (1856-1937), who was a singer, poet, and critic at the music journal L'art musical. Their relationship deepened over a shared love of music and poetry, and they collaborated on mélodies, set to Hettich’s poems.8 Géliot writes, “[Hettich] was to become an influential and decisive figure in the life of Mel Bonis and in her relationship to the world of voice.”9 In 1884, "Villanelle" and "Sur la plage," mélodies with texts by Hettich, would be Bonis' first published works.10

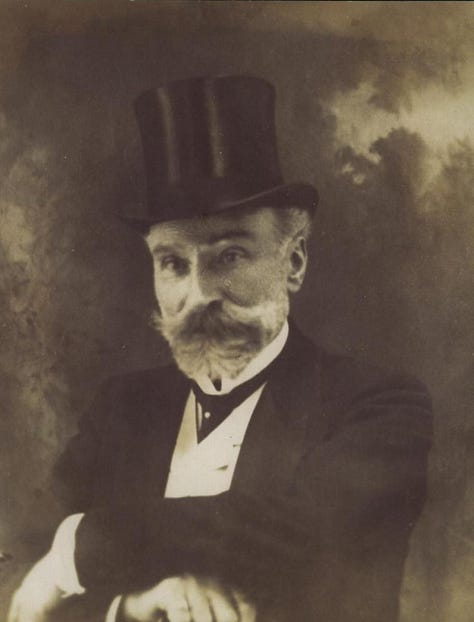

In 1881, Bonis’ parents rejected Hettich’s marriage proposal, and Bonis was forced to abandon her studies at the Conservatoire to sever their relationship. In 1883, at twenty-five years old, she wed industrialist Albert Domange (1836-1918), who was twenty-two years her senior with five children. It was an arranged marriage, one which raised the social standing of the Bonis family. Together, Bonis and Domange would have three children, and she assumed a new identity, that of “Madame Albert Domange,” managing her household in a mansion in Paris, now a wealthy bourgeois wife and mother of eight.11

In Souvenirs et Refléxions, Bonis recounts her fascination with dreams. She believed dreams to be potential representations of truth, whether of our innate desires and worldly experiences, or as harbingers of future events. Here, Bonis relates a recurrent dream, which opaquely references the perceived incompatibilities between her “personas,” that of Bonis as a committed society wife and Bonis as an independent artist.

I saw my sister in a dream in the form of a statue (not completely inanimate, but immobile, placed on a pedestal, hung on the wall). She was much larger than life, her face very altered, her gaze fixed anxiously on a clock. I felt that she was in great pain and that time seemed terribly long to her. She uttered these words: ‘Mrs. Albert Domange’ ... This dream had an enormous impression on me; I will not be deprived of the idea that it has a meaning. Where my sister is, she is not free; inert, she suffers her fate… Why ‘Mrs. Albert Domange’ rather than ‘Mélanie’???12

While Bonis’ dream portrays the lifeless statue as her sister, who also married a wealthy entrepreneur, I am reminded of Bonis herself and the cage-like comforts of her bourgeois life. Perhaps, this explains her sister’s stark warning to “Mrs. Albert Domange" and not “Mélanie,” that if Bonis allowed social convention to subsume her identity as an artist, she too could find herself frozen in time as an adornment on the wall.

Due to her husband’s lack of interest in her music and domestic obligations, Bonis composed little in the first decade of her marriage. However, she never abandoned her musical calling, and Bonis continued to revise compositions and communicate with her Conservatoire professors.13 In 1891, Bonis submitted Les Gitanos, valse espagnole, op. 15 to a valse competition with the journal Piano Soleil. After winning first prize and having her score published in other journals, Bonis was inspired to resume her musical endeavors.14

Throughout her life, Bonis sought to develop her musical career by competing in competitions, maintaining close relationships with publishers, namely Leduc, Demets, and Eschig, and becoming a member of professional organizations to network with other musicians. Bonis won first prize in 1899 and honorable mention in 1904 for her harp compositions with the Société des Compositeurs de Musique, and she served as a member of the Société from 1899 to 1911. In 1910, Bonis served as the first woman secretary of the organization.15

With a newfound momentum, Bonis began to compose more and more, primarily from 1892 to 1914. She ultimately produced 300 compositions, including solo piano works, mélodies, organ works, choral works, chamber music, and orchestral pieces. Géliot writes, "The most striking thing is the discrepancy between the moral rigidity of 'Madame Domange,' obsessed by her social duties and steeped in piety, and the extraordinarily bold sensuality which emerges from the musical works that she produced under her pseudonym."16

Cello Sonata in F major, op. 67 with cellist Tanya Tomkins and pianist Eric Zivian | Left Coast Chamber Ensemble (2021-2022)

In the 1890s, it was at the office of her publisher, Alphonse Leduc (1804-1868), where Bonis would encounter Hettich once more. He was now married and a professional singer and vocal pedagogue. Hettich still wrote for L'art musical, who owned the Leduc publishing house. Hettich encouraged Bonis to pursue her musical career, and they resumed their friendship with meetings at her publisher's office. Hettich also supported Bonis with introductions at salon gatherings, where she performed her music and met potential artistic collaborators.

During this period, mélodies drew the two musicians together yet again. Hettich offered Bonis his newest poem, "Noël Pastoral," and weeks later, she set it to music. "Noël Pastoral" was Bonis' first mélodie published by Leduc.17

The Secret Loves of Mel Bonis

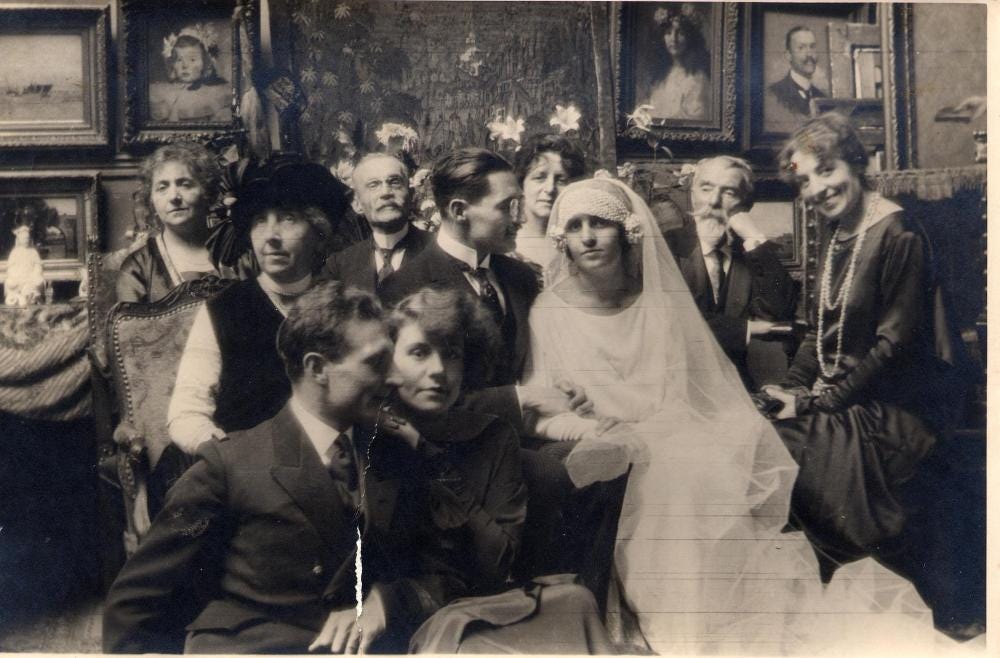

After resuming their friendship in the 1890s, Bonis and Hettich fell back in love once again. Their clandestine romance led to the 1899 secret birth of their daughter, Jeanne-Pauline-Madeleine Verger; Bonis was forty-two years old. To conceal her pregnancy, Bonis stayed alone at her estate in Sarcelles and later in Switzerland, telling family that she needed medical treatment for an ailment.18

The baby was placed in the home of Bonis’ former maid, who would later raise the child as a foster parent. Without admitting to the affair, Bonis would never be able to recognize her daughter legally.

After Madeleine’s birth, Bonis distanced herself from Hettich and the societal dishonor that their relationship would bring. She managed her daughter’s affairs from a distance, supporting Madeleine's education at boarding school. After the death of his wife, Hettich was finally able to recognize Madeleine legally as his daughter; she was thirteen years old.

Due to her affair and Madeleine's secret birth, Bonis became tormented by the shame of transgressing her Catholic beliefs. She began to suffer bouts of depression and exhaustion, which worsened in her later years. Bonis turned to composition to exorcise her demons, although the outbreak of World War I led to an eight-year hiatus in her musical activities.19

Upon her husband’s death in 1918, Bonis invited Madeleine on summer holidays with her children. Throughout Madeleine's childhood, Bonis presented herself as a "godmother" figure, visiting the child at Hettich's home when she returned on school breaks. Tragedy, however, loomed large. Bonis' son, Édouard, now returned from the horrors of war, confessed his love for Madeleine, who unbeknownst to him was his half-sister. Ultimately, Bonis was forced to reveal Madeline’s true parentage, although the family kept the matter secret for several generations due to social stigma.

Madeleine and Édouard separated, later marrying other partners, and having families of their own. Madeleine maintained a life-long relationship with Bonis, but it remained forever altered by the revelation of her secret birth. Géliot posits that Bonis’ children, like the composer herself and Hettich, may never have truly healed from the trauma of their forbidden romance.20

From 1922 to 1937, the last fifteen years of Bonis' life, she lived more and more in isolation, composing in her studio and spending time in prayer. Bonis' retreat from society into spiritual contemplation was also reflected in her engagement with sacred music; she now composed primarily organ and choral works. Although Bonis attempted to promote her newest compositions with publishers, the composer found that her musical style was now considered unfashionable, even conservative. The compositions of her final years would not be published until the end of the twentieth century.21

The Legacy of Mel Bonis

It is important to note that, while Bonis lacked certain freedoms in her life, her artistry was not completely stymied. Instead, the composer found herself encased in gendered socio-cultural expectations to which she continually subordinated her creative desires. Bonis simultaneously labored under the weight of societal indifference and a lack of investment in her musical efforts, which, although she had access to education, wealth, and status, inevitably inhibited her career. This pernicious indifference manifested itself in Bonis' life from childhood, from her parents, her husband, and later her publishers, and it persisted after her death.

The trajectory of Mel Bonis' legacy is a story of neglect, preservation, and ultimately, advocacy. Like so many women composers of her era, Bonis' music was "forgotten" after her death in 1937, a cultural forgetting that was precipitated by the devastations of World War II and shifting compositional styles throughout the twentieth century that made her music unpopular. In the aftermath of World War II, Bonis' eldest children, Pierre Domange and Jeanne Brochot, collected her unpublished works, submitting her catalogue to the Société des auteurs, compositeurs et éditeurs de musique. Publishers, however, showed little interest in publishing (or republishing) her compositions, and many of the copyright permissions were ultimately returned to the Bonis family.22

Christine Géliot recounts her moving experience of rediscovering her great-grandmother's musical legacy through the tenacity of a stranger, German cellist Eberhard Mayer. In the 1990s, Mayer discovered one of Bonis' string quartets, and he committed himself to finding out more about the composer. At that time, there was little to no publicly available information about Mel Bonis. In 1997, he was connected to Yvette Domange, Géliot's aunt, who had preserved Bonis' archive in her basement. Yvette Domange asked her niece for assistance in organizing materials for Mayer's visit, and Géliot, a professor of piano, directly engaged with her great-grandmother's legacy for the first time. She became a passionate advocate for Bonis' music and founded the Association Mel Bonis, which is now responsible for publishing and advocating for the composer's musical works. Géliot also has written the only comprehensive biography of the composer.23

To read more on the incredible work of Géliot and the Association Mel Bonis in championing Bonis and preserving her legacy, click here.

The mélodies of Mel Bonis

Bonis' musical education was shaped by a resurgence of nationalist sentiment in France, caused by the 1871 defeat of Napoleon III in the year-long Franco-Prussian War. To reject Germanic cultural influences, composers sought to create a specifically "French" musical style. Ultimately, no one compositional style coalesced. Rather, a variety of compositional movements blossomed, informing one another, such as late Romanticism, Neoclassicism, and Impressionism.24

Géliot argues that Bonis was most influenced by post-Romantic French composers Franck, Saint-Saëns, and Gabriel Fauré and remained committed to tonality and Classical form. However, she still cultivated her own unique harmonic and rhythmic languages, particularly adhering in her mélodies to the rhetoric of her French texts.25 Bonis’ music also incorporated Impressionist sensibilities by evoking mood and atmosphere through extended harmonies.

Bonis ultimately composed forty songs, and she selected poetry from several authors, including Amédée Landély Hettich, Maurice Bouchor, Edouard Guinand, Victor Hugo, Anne Osmont, Madeleine Pape-Carpantier, and Bonis herself under pen names. Throughout her song repertoire, Bonis engaged with multiple themes and styles, including light character sketches, love songs, and sacred meditations.26

Viens! (Come!) by Mel Bonis with mezzo-soprano Sharon Carty and pianist Una Hunt

Recorded at the Drogheda Arts Festival in 2022

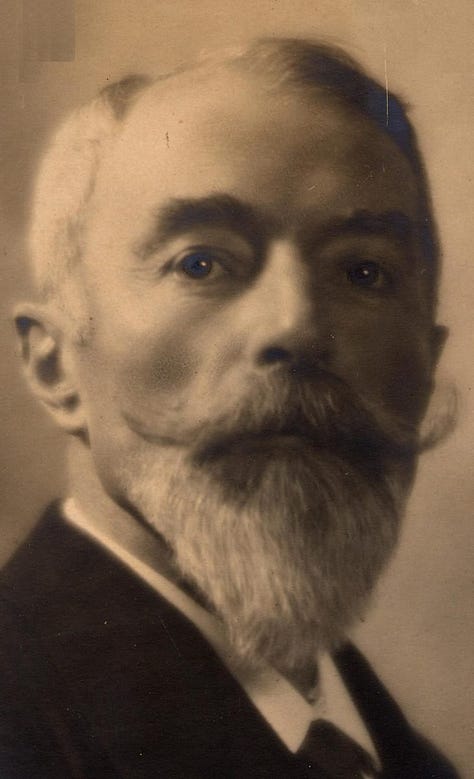

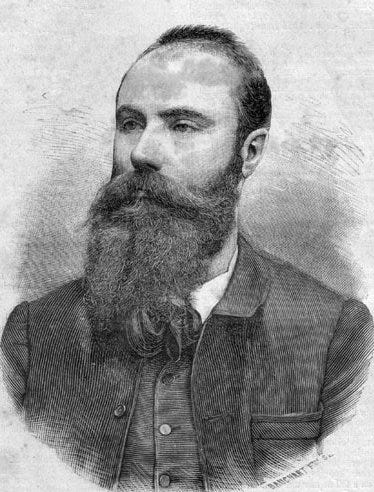

Maurice Bouchor (1855-1929)

In Trois Mélodies, op. 91, composed in 1912 and published for the first time in 2001, Bonis chose contemporary poetry of French poet, playwright, and puppeteer Maurice Bouchor. Bonis’ set of three songs includes poems from Bouchor’s 1895 collection Les symboles, nouvelle série (The Symbols, New Series). Bonis was not alone in her fascination with Bouchor’s poetry; notable mélodie composer Ernest Chausson (1855-1899) set over thirty of Bouchor’s texts to music.

In an 1893 society editorial in The New York Times, an unknown author discusses Bouchor’s upcoming trip to New York City, offering unique insight into the poet’s character, appearance, and public persona.

[Bouchor] is thirty-eight, tall, and an evidence of the theory formulated by Delacroix that nature is a romanticist … Nature gave to him the graces of a beard long and soft as that of the antique Scamander River… He is studying Buddhism assiduously, is a vegetarian, and practices, with evident pleasure, a life of Carthusian austerity. If he were not a celebrated poet, he might be famous for the special charm of his personality.27

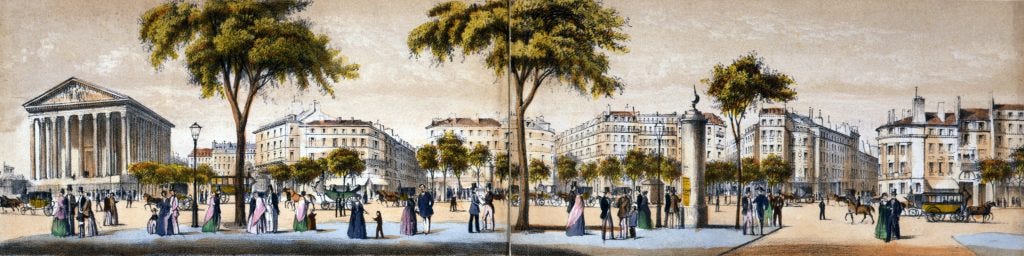

Born in Paris and educated at the Lycée Louis-le-Grand, Bouchor published his first poetry collection, Les Chansons Joyeuses (The Joyful Songs), at nineteen years of age. It was an instant success, and he continued to publish poetry in both prose and verse between 1874 and 1880.

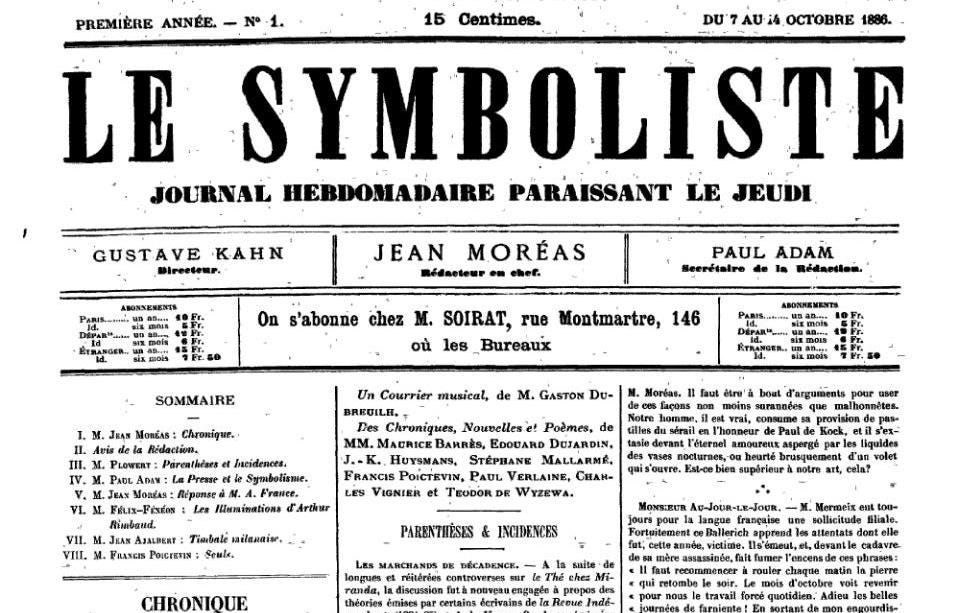

Inspired by Catholicism and religious mysticism, Bouchor was influenced by the late nineteenth-century Symbolist literary movement in France. By rejecting aesthetics of naturalism, Symbolists endeavored to represent absolute truths figuratively via metaphorical language and images. With an emphasis on evoking symbolic imagery, rather than depicting a subject realistically, Symbolist adherents ultimately believed that symbols could reveal details of the poet’s psyche.

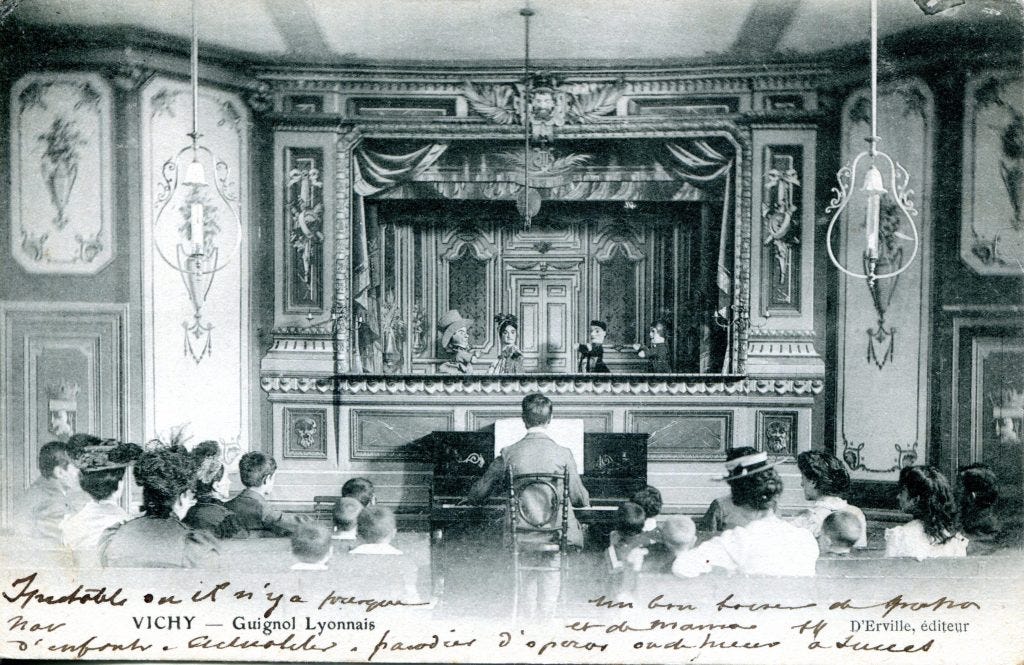

With the artist collective “Les Vivants” (The Living), Bouchor also designed puppets and wrote scripts for original marionette plays, which were performed at the Petit de la Galerie Vivienne in Paris. Although the theatre only survived from 1889 to 1892, it is considered one of the first theatrical venues of the Symbolist movement in France.28

Trois Mélodies, op. 91

Bonis composed Trois Mélodies in 1912, years after her affair with Hettich had ended and several years prior to revealing to her daughter the facts of Madeleine's birth. Musically, Trois Mélodies represent a composer in total command of her compositional aesthetic, as she deftly enlivens a series of dense, and often impenetrable metaphors about love. Since mélodies played such a pivotal and enduring role in Bonis' relationship with Hettich, we can potentially imagine these songs as a reflection of Bonis' own romantic journey with Hettich and their daughter.

In Trois Mélodies, Bonis excerpts three Bouchor texts that obsess over the glorious Viola, who both charms and haunts the poet. Viola may reference Shakespeare’s shipwrecked protagonist from Twelfth Night, who disguises herself as a male page, only to fall in love with the duke that she serves. Bouchor had a fascination with the works of William Shakespeare (1564-1616), and he translated several plays for performances at the marionette theater, as well as published Les Chansons de Shakespeare (The Songs of Shakespeare) in 1896.

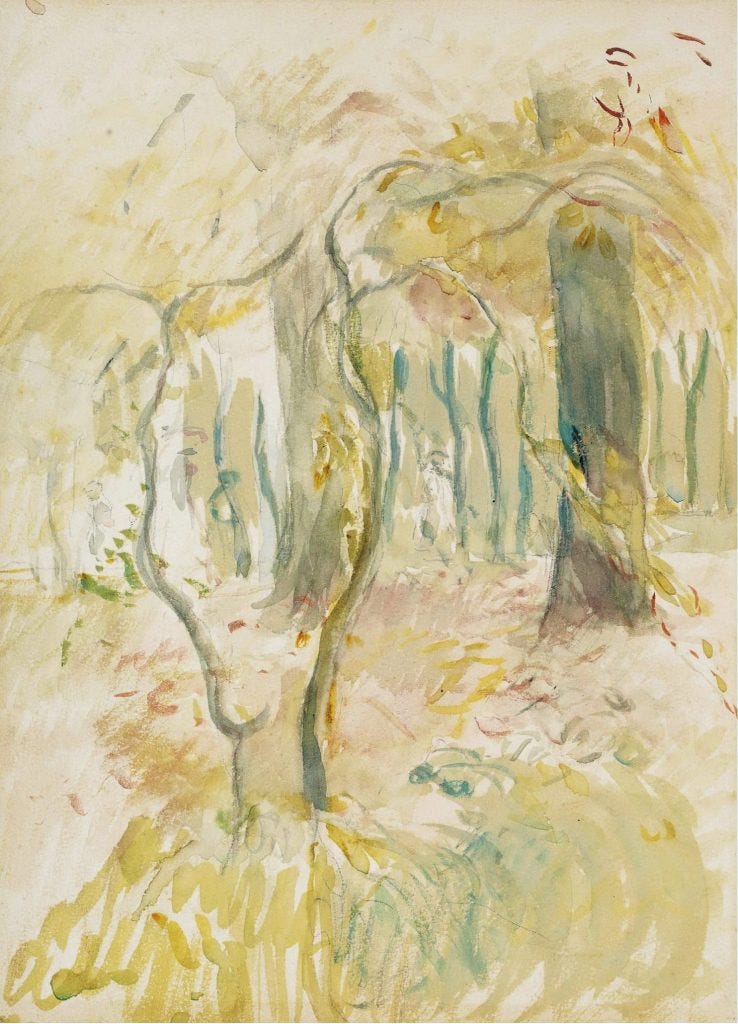

Since Bouchor's Shakespearean reference is oblique at best, I prefer to funnel the poetic and musical ideas of Trois Mélodies through the paintings of French artist Berthe Morisot (1841-1895), a founder of Impressionism in visual art and another often-overlooked woman artist of Bonis' era.

i. Viola

In the opening song of Trois Mélodies, entitled “Viola” by Bonis, the protagonist acknowledges that they have hardly “glimpsed” at their beloved. Regardless, Viola soon dissolves into a series of metaphors: her eyes mirror the shining skies, her smile embodies tenderness and immortality. Such descriptions of Viola are nebulous, as if from a dream. In fact, they paint a more vivid portrait of the poet’s state of mind than of an actual living, breathing Viola. Still, as Bonis sets the text over swinging waltz-like phrases with indicated rubato (a tempo’s give-and-take), the poet’s unrequited affections seem to cause little pain. In fact, the protagonist appears ebullient, thoroughly enjoying their metaphorical Viola from a distance.

i. Viola

Viola, ton sourire et tes yeux caressants

Où le ciel curieux et ravi se reflète;

Ton sourire et tes yeux, ma fraîche violette,

Chantent l'inaltérable amour que je pressens.

O toi que j'entrevis à peine, ton sourire

Me parle de tendresse et d'immortalité;

Je [veux]* t'aimer, je t'aime, et me voici hanté

Par tes yeux où le ciel émerveillé se mire.

J'évoque en ce moment tes cheveux blonds et fins,

Tes yeux, ta joue en fleur que je n'ai point baisée,

Ton sourire et, dans la lumière irisée,

J'abandonne mon âme à des songes divins.

*[] denotes alteration to text by Bonis

i. Viola

Viola, your smile and your gentle eyes

Are mirrored in the intriguing and rapturous sky;

Your smile and your eyes, my sweet little violet,

Sing of the steadfast love that I foresee.

Oh you, whom I barely glimpse at, your smile

Speaks to me of tenderness and of immortality;

I want to love you, I love you, and I have been haunted

By your eyes, in which the sky, enthralled, gazes at itself.

I recall in this moment your blonde, fine hair,

Your eyes, your flushed cheek that I did not kiss,

Your smile and, in the iridescent light,

I abandon my soul to divine dreams.

Translation by Noelle McMurtry

ii. Sauvez-moi de l’amour (Save me from love)

In “Sauvez-moi de l’amour” (Save me from love), the second song of Bonis’ set, the poet’s mindset has drastically altered. They are now trapped, lost within a “thicket” of unrequited love. Thorns, brambles, and bushes cut at their skin, drawing blood. The poet, however, thinks little of this pain in comparison to what Love has forced upon them. They have been "seized" by Cupid, who causes “pointless suffering” as the poet wanders through the wilderness of their own tangled emotions. Bonis’ piano accompaniment employs fluid arpeggiations to create drama in the musical line, and she uses shifting meter and tempos to reflect the poet’s unstable mental state. “Sauvez-moi de l’amour” is also an excellent example of Bonis’ text-setting capabilities, and she chooses dotted rhythms and sixteenth notes to articulate the subtle inflection and flow of her French text.

ii. Sauvez-moi de l’amour

Sauvez-moi de l'amour, taillis où je m'enfonce,

Églantiers épineux qui déchirez mes doigts,

Baisers sauvages de la ronce,

Insectes altérés et cruels de [nos]* bois!

Plus de vains rêves, plus de saintes fiançailles!

Je me suis trop créé de stériles douleurs;

Dans les ténèbres des broussailles

J'oublierai l'île vierge et ses plaines de fleurs.

Ah! comment croire encore au songe magnifique?

Car le brutal Enfant vient de me ressaisir,

Et la vision séraphique

S'évanouit au souffle ardent de mon désir.

N’espère pas tromper la puissante nature

Si tu nourris en toi le plus timide amour

Tu seras bientôt sa pâture

Où le coeur a frémi Eros aura son tour.

Dan les buissons aigus je me fraie un passage

Arbustes emmêlés qu’ignore le soleil

Frappez moi, cinglez mon visage,

Et faites ruisseler à flots mon sang vermeil.

*[] denotes alteration to text by Bonis

ii. Save me from love

Save me from love, this thicket where I am stuck,

Thorny wild roses that prick my fingers,

Fierce kisses from the blackberry bush,

Distorted and cruel insects of [our] woods!

More than vain dreams, more than saintly betrothals!

I am too defined by pointless suffering;

In the darkness of the undergrowth

I will forget the virgin island and its meadows of flowers.

Ah! How do I still believe in this magnificent dream?

Because cruel Cupid comes to seize me,

And this angelic apparition

Vanishes in the ardent breath of my desire.

Do not dare to deceive Love’s powerful nature

If you nourish the feeblest affection by it

You will soon be its lifeblood

Where, with your trembling heart, Cupid will have his turn.

In the sharp bushes, I make my way

Tangled shrubs, ignored by the sun

Hit me, slap my face,

And let my vermilion blood flow freely.

Translation by Noelle McMurtry

iii. Vers le pur amour (Towards pure love)

“Vers le pur amour” (Towards pure love) concludes Trois Mélodies with a return to radical acceptance. The poet, now floating on a metaphorical boat towards a “happy island of mystery,” has reconciled the turbulence of their prior emotions. Now, they sail on the waves of their dreams. The poet calls out to Viola one last time, hoping to meet her on this island, although sadly in dreams, nothing is assured. Notably, Bonis employs a modified strophic form, in which groups of two stanzas are set to identical music. After the through composed, shifting gestures of the first two songs in op. 91, this repetitive musical framework creates a sense of closure to the poet’s journey. Bonis has deftly crafted a musical arc that portrays the unrelenting, stormy, and ecstatic nature of love itself, from first glance to final farewell.

iii. Vers le pur amour

Guidé par de beaux yeux candides

Dans ma barque féerique aux reflets d'argent fin

Vers l'Amour je voudrais faire voile sans fin

Sur des rêves bleus et splendides.

Vers l'Amour dont le souffle frais

Berce des champs de fleurs dans une île enchantée,

Et qui, pour apaiser mon âme tourmentée,

M'ouvrira de saintes forêts.

[Et plus tard quand], loin de la terre,

O Viola! Guéris des brûlantes langueurs,

Nous irons caresser les songes de nos coeurs

Dans l'île heureuse du mystère?

Dans le libre ciel des Esprits

Quand nous aurons [quitté]* la nature [mortelle],

Ne goûterons-nous pas une paix éternelle?

Rêveusement tu me souris.

*[] denotes alteration to text by Bonis

iii. Towards pure love

Guided by beautiful, innocent eyes,

In my magical boat with flashes of fine silver

Towards Love, I would like to sail time and time again

On blue and splendid dreams.

Towards Love, whose fresh breath

Cradles the fields of flowers on an enchanted island,

And who, to appease my tormented soul,

Reveals to me its holy forests.

[And later when], far from the earth,

Oh Viola! Healed by blazing languor,

Will we caress the dreams of our hearts

On the happy island of mystery?

In the liberated heaven of the Spirits,

When we abandon our mortal form,

Will we not enjoy an eternal peace?

Dreamily, you smile at me.

Translation by Noelle McMurtry

Watch and listen to our January 2023 performance of Trois Mélodies with pianist Hui-Chuan Chen at Peabody Institute.

In the final stanza of “Vers le pur amour,” Bonis sets the text:

In the liberated heaven of the Spirits,

When we abandon our mortal form,

Will we not enjoy an eternal peace?

Dreamily, you smile at me.

If we consider Trois Mélodies as an entry in Bonis' diary, these final words signify her belief in an afterlife, a realm in which Bonis could finally seek forgiveness and be reunited with those she loved so fiercely.

Trois Mélodies, however, also reveal the emotions of a woman and composer who very much lived; hers was a passionate, full, and multi-faceted life, despite the dictates of French society’s gendered prejudice. Bonis’ mélodies endure as powerful indicators of this spirit, endowed with her creativity and unique compositional voice.

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Christine Géliot and the Association Mel Bonis for their feedback on this article, as well as granting their permission to include photographs from the collection in this post.

Bibliography

“A Visit from a French Poet: Maurice Bouchor Now In This City – His Appearance and His Work.” The New York Times. June 13, 1893. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1893/06/13/issue.html.

Beasley, Bryanna. “Musical Multiplicities: The Lives and Reception of Four Post-Romantic Women.” MM thesis., University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2021.

Bonis, Mel. Souvenirs et Réflexions. Évian: Éditions du Nant d’Enfer, 1974.

Géliot, Christine. “Mel Bonis, Composer: Biography.” English translation by Florence Launay and Michael Cook. 2023. https://www.mel-bonis.com/EN/Biographie/.

Géliot, Christine. “Compositions for voice by Mel Bonis, French woman composer, 1858-1937.” Journal of Singing 64, no. 1 (2007): 47.

Géliot, Christine. “Mel Bonis et les Melodies.” Les Melodies: Volume II. Paris: Editions Fortin Armiane, 2014.

Lecucq, Evelyne. “Maurice Bouchor.” World Encyclopedia of Puppetry Arts. 2009. https://wepa.unima.org/en/maurice-bouchor/.

Padilla, Geraldine Margaret. "A Study on the Compositional Style of the Flute Chamber Works of Mel Bonis." PhD dissertation., University of Southern Mississippi, 2018.

Polomé, Anne-Marie. “Portrait de compositrice: Mélanie-Hélène Bonis dite Mel Bonis.” Crescendo Magazine. May 26, 2021. https://www.crescendo-magazine.be/portrait-de-compositrice-melanie-helene-bonis-dite-mel-bonis-i/.

Tsou, Judy. "Bonis, Mélanie (Hélène)." Grove Music Online. 2001. https://www-oxfordmusiconline-com.proxy1.library.jhu.edu/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000045497.

Wikipedia contributors. "Maurice Bouchor." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Last updated on September 23, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Maurice_Bouchor&oldid=1176663849.

Anne-Marie Polomé, “Portrait de compositrice: Mélanie-Hélène Bonis dite Mel Bonis.”

Bonis, Souvenirs et Réflexions, translated by Noelle McMurtry, 34.

Polomé, “Portrait de compositrice.”

Judy Tsou, "Bonis, Mélanie (Hélène)."

Polomé, “Portrait de compositrice.”

Christine Géliot, “Compositions for voice by Mel Bonis, French woman composer, 1858-1937,” 50.

Polomé, “Portrait de compositrice."

Padilla, "The Flute Chamber Works of Mel Bonis," 12.

Géliot, “Compositions for voice,” 47.

Padilla, "The Flute Chamber Works of Mel Bonis," 16.

Géliot, “Mel Bonis, Composer: Biography.”

Bonis, Souvenirs et Réflexions, translated by Noelle McMurtry, 14.

Géliot, “Mel Bonis, Composer: Biography.”

Padilla, "The Flute Chamber Works of Mel Bonis," 15.

Ibid., 16.

Ibid., 18.

Ibid., 16.

Ibid., 18.

Géliot, “Mel Bonis, Composer: Biography.

Padilla, "The Flute Chamber Works of Mel Bonis," 20.

Ibid., 4.

Géliot, “Compositions for voice,” 48.

Padilla, "The Flute Chamber Works of Mel Bonis," 3.

Géliot, “Compositions for voice,” 52.

Ibid., 50.

Ibid., 53.

“A Visit from a French Poet,” The New York Times, 1893.

Evelyne Lecucq, “Maurice Bouchor.”

This story is insane! Her life would be an incredible movie. It’s amazing to me how fragile these women composers’ creative lives were/are ... their body of work nearly buried and forgotten at every turn and just narrowly discovered. Imagine how many women’s work are lost. ...Historians save the day! It’s an essential service to make sure we don’t lose it.